Inside L00K: Sales-Leaseback Syndications

Sale-leasebacks are actively used by operating businesses to free trapped capital. In peak years, companies have completed hundreds of sale-leaseback transactions totaling over $30 billion annually, converting owned facilities into liquidity while continuing to operate under long-term leases.

Investors step into the ownership side of that equation, collecting rent while operators keep control.

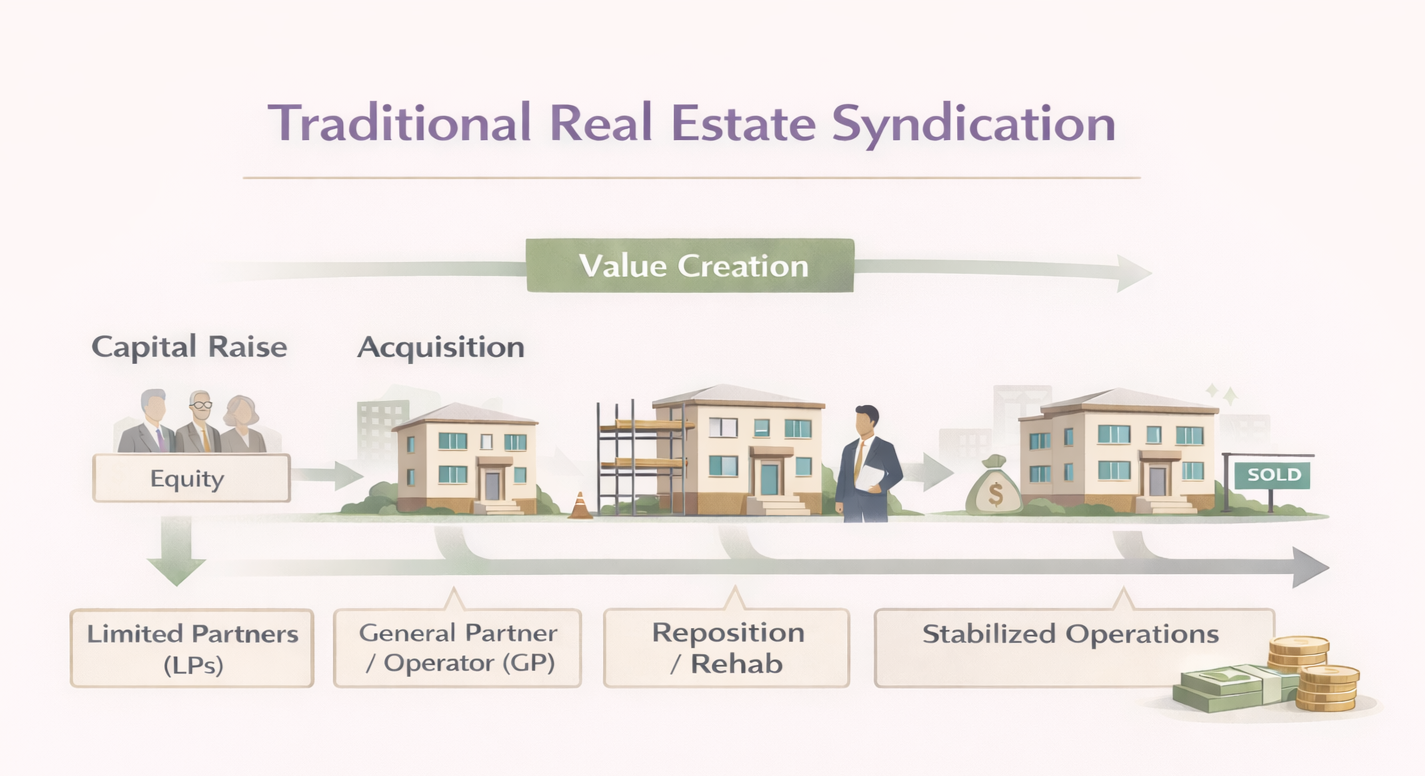

To understand why sale-leasebacks are different, it helps to understand the traditional real estate syndication model.

How Most Real Estate Syndications Work

Typical real estate syndications are a type of investment strategy in which a group of investors pool their resources to purchase, manage, and operate income-producing real estate properties.

The general partner (GP) is responsible for acquiring, managing, and operating the properties, while the limited partners (LP) provide the capital to fund the purchase and ongoing operations. The limited partners receive a share of the profits generated by the properties and benefit from the appreciation of the real estate assets.

This strategy allows investors to participate in real estate ownership and operations without having to manage the property themselves. It also provides access to larger and more diversified real estate investments that would otherwise be beyond the reach of individual investors.

- Sponsor acquires the property using bank loans + private equity.

- Improves the property and operating processes.

- Exits the property at a profit, typically over a 3–5 year period.

- Seller steps away without needing to update or remodel.

- Buyer (Sponsor) creates value through optimization and upgrades.

- Investors receive cash flow with favorable tax treatment.

- Tenants gain a better place to call home.

Sale-Leaseback Syndications

A few years back I discovered (and eventually invested in) an interesting variant to this model: Sale-Leaseback (SLB) syndications.

Sale-leaseback syndications are a type of financing structure in which an owner of real estate property sells the property to the sponsor and then leases it back for continued use.

The owner receives a lump sum of cash from the sale of the property, which can be used for a variety of purposes — such as paying off debt, financing growth, or returning capital to investors.

How a Sale-Leaseback Works

In a sale-leaseback syndication, the sponsor buys the property and leases it back to the original owner. The lease is typically structured as a fixed rental rate with annual increases and a predetermined long lease term (typically 10+ years).

SLBs are often used by companies that own real estate that is critical to their operations, but that they no longer need to own. By selling the property and leasing it back, the company can free up capital while still retaining access to the property and the use of its facilities.

The buyer (sponsor) generates income from the lease payments and profit when the property is sold.

Key idea: ownership changes hands, operations stay put — the tenant keeps using the facility under a long-term lease.

Get Back9 Signals →

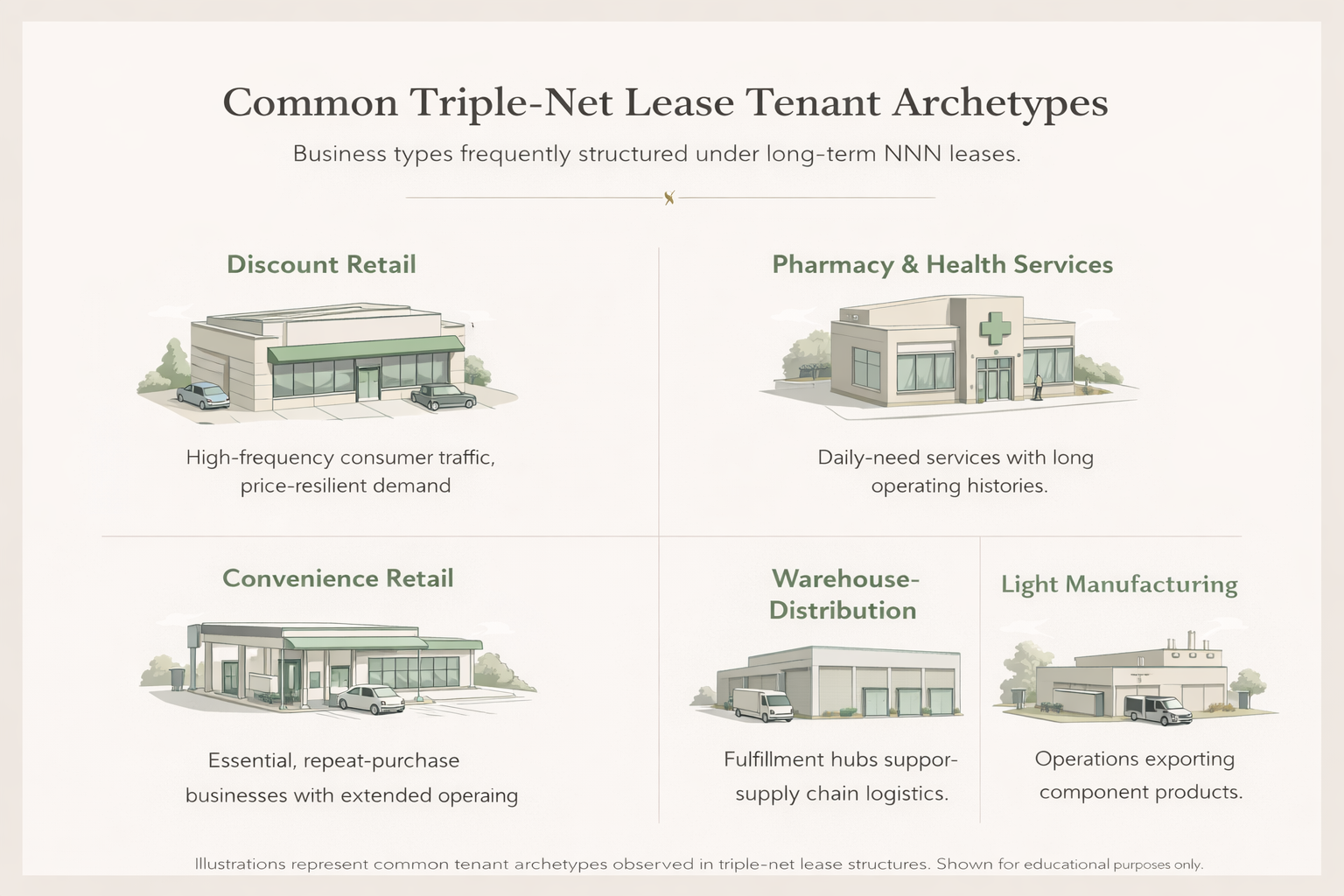

While the transaction is unique, the lease that follows often isn’t. In many sale-leaseback structures, the operating business that sells the real estate simply becomes a long-term tenant, signing a familiar NNN lease similar to those used across other essential, cash-generating business models.

Important distinction:

A sale-leaseback describes the transaction.

The triple-net lease describes the income behavior that follows.

What the Lease Looks Like After the Sale

The most common revenue model for SLB syndications is a triple-net (NNN) lease structure, where the tenant is responsible for paying all of the operating expenses associated with the property:

NNN (Triple-Net) in plain English: the tenant pays the operating costs.

- Property taxes

- Insurance

- Maintenance / repairs

In this model, the tenant typically agrees to a long-term lease agreement, ranging from 10 to 25+ years, and the rental rate is based on market conditions and the operating expenses associated with the property.

Typical NNN leases also have built-in annual rent increases (2%-3%) to reflect increasing future market lease rates.

Who Typically Signs These Post-Sale Leases ?

Benefits

Sale-leaseback syndications can offer a number of benefits to both the tenant and the investors.

For the Tenant

- Capital generation: The tenant can receive a lump sum of cash from the sale of the property, which can be used for paying off debt, financing growth, or cost-intensive capital improvements.

- Improved balance sheet: By selling the property, the tenant can reduce its debt-to-equity ratio, improve financial flexibility, and increase borrowing capacity.

- Continuity of operations: The tenant can continue to use the property under a long-term lease, ensuring operations are not disrupted.

For the Sponsor / Investor

- Income generation: Investors can receive a steady stream of rental income from lease payments, providing a stable return.

- Diversification: Investors can diversify their portfolio by including real estate investments, providing a hedge against inflation and market volatility.

- Real estate exposure: SLBs provide exposure to real estate with potential for long-term capital appreciation.

Risks

Sale-leaseback syndications, like any financial transaction, can have some potential problems and risks that must be considered. Some of the most common challenges and risks include:

Sale-leasebacks aren’t risk-free, but the risks tend to be identifiable, underwritable, and tied to fundamentals rather than speculation.

- Tenant credit risk: The success of an SLB depends on the tenant’s ability to pay rent and fulfill lease terms. Financial distress can reduce or interrupt income.

- Interest rate risk: Rising rates can compress property values, impacting exit pricing even if cash flow remains stable.

- Lease termination risk: Early termination can result in lost income and the need to re-tenant the property.

- Market conditions risk: Broader real estate market shifts, including declining values or increased competition, can affect valuation.

How to Mitigate the Risks

The main factors in an SLB are the long-term financial health of the tenant and the fundamental value of the property on the open market. There are three main areas to consider:

Experienced sponsors focus on three underwriting pillars:

- Tenant overall credit: Assess long-term financial health, access to capital, and vulnerability to economic cycles — at acquisition and quarterly thereafter.

- Business-unit performance: Review unit-level financials across locations to understand performance trends and concentration risk.

- Re-tenanting realism: Underwrite the property’s appeal to alternative tenants at market rents if the lease needs to be reset.

A Little History…

Early industrial facilities were among the first assets used in sale-leaseback structures, prized for operational necessity and reliable rent.

The history of sale-leaseback syndications traces back to the early 20th century, when companies began using the structure to raise capital while continuing to operate mission-critical facilities. Early SLBs focused heavily on industrial properties, factories and warehouses, viewed as stable, necessity-driven sources of rental income.

Over time, sale-leasebacks expanded into retail, office, and multifamily assets, fueled by tax law changes, increased real estate liquidity, and the growth of REITs. While the 2008 financial crisis slowed activity, the market recovered and continued to mature.

Today, sale-leasebacks are used by companies of all sizes and across industries to raise capital, reduce balance sheet strain, and improve financial flexibility.

Who Typically Invests in Sale-Leaseback Deals?

- Institutional investors: Pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments favor SLBs for long-duration income and stability.

- Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs): Use SLBs to access operational real estate and diversify portfolios.

- High-net-worth investors: Family offices and private equity groups seeking income-producing real assets.

- Retail investors (folks like you & me): Participate via syndications for stable cash flow and long-term exposure.

Are SLB Return Profiles Similar to Multifamily Deals?

Sale-leasebacks and value add multifamily target different levers, but they can produce surprisingly similar income profiles.

The superpower of sale-leasebacks is that lease terms and annual rent increases are baked in, producing highly predictable cash flow — while triple-net structures shift taxes, insurance, and maintenance to the tenant.

The tradeoff for all this safety and simplicity is a slightly lower overall return, but the predictable — and higher day one cash-on-cash distributions — can be very attractive.

What Types of Companies Use Sale-Leasebacks?

Companies across a wide range of industries may use sale-leasebacks as a way to raise capital, reduce debt, and improve their balance sheet — while still maintaining control of their operations.

- Manufacturing: factories, warehouses, distribution facilities

- Retail: big-box stores and shopping centers

- Healthcare: hospitals, medical centers, specialized facilities

- Technology: office buildings and data centers

- Government: buildings and infrastructure

- Financial: banks and insurers that own operational real estate

Sale-leasebacks don’t eliminate risk — they relocate it into contracts.

Final Thoughts

There is no right or wrong with a sale-leaseback. It is a financing structure that may be a great option for one company, but less than ideal for another. Businesses looking to grow and expand — who own the real estate from which they operate — can benefit from a sale-leaseback and the associated capital injection.

As a passive investor, the day-one higher cash-on-cash returns and reliable long-term cash flow can be an attractive option. For investors who prioritize super predictable cash distributions, SLB syndications might just be worth a look.

If you are interested to learn more about my experience with sale-leaseback syndications let’s talk.

This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or an offer to sell securities.